Dark Web Search Engines in 2025: A Cybersecurity Defender’s Guide

- Fragmented Search Landscape: Dark web search is dominated by Tor based search engines on the Onion network, with a handful of notable platforms e.g. Ahmia, Torch, Haystak serving as primary gateways in 2025. I2P search remains niche and less developed, reflecting Tor’s much larger user base.

- Safety vs. Scope Trade off: Search engines vary widely in content filtering and scope. Ahmia and similar ethical engines filter illicit content e.g. block CSAM and malware for safer use. In contrast, Torch and Haystak index almost everything on millions of .onion pages, maximizing coverage but exposing users to risky content.

- Differing Philosophies: Some engines emphasize privacy and transparency Ahmia is open source and respects opt out protocols, while others like Torch take a no censorship stance, showing uncurated results alongside aggressive advertisements. Freemium models have emerged e.g. Haystak Premium offers advanced search features and historical archives to paying users.

- Common Use Cases Defensive: Security teams and threat intelligence analysts use these search tools to discover leaked credentials, confidential data, or chatter about their organization on hidden forums. For example, a penetration tester might search employee passwords or company names on Ahmia or Haystak to assess exposure. Ransomware researchers monitor data leak sites via search engines to track victim postings and stolen data circulation.

- OPSEC and Legal Risks: Using dark web search engines carries operational security risks. Unfiltered results can lead to malware laced pages or illegal content with a single careless click. Analysts must use hardened setups Tor Browser in safest mode, no scripts and avoid downloading files. All activities should comply with the law and corporate policy. These tools are for monitoring threats, not engaging in illicit trade.

- Monitoring & Enforcement: Law enforcement increasingly monitors dark web indices. Major crackdowns e.g. Operation RapTor in 2025 targeted darknet drug markets, resulting in 270 arrests and over $200 million seized. After such takedowns, criminal vendors scattered to smaller sites driving a surge in searches as buyers tried to locate new vendor URLs. Investigators pay close attention to search queries that spike after marketplace closures, as they can reveal emerging hot spots.

- Global Accessibility: Dark web search engines are globally accessible wherever Tor is used, but regional differences exist. Western language content English dominates most indices. Some regions with heavy Tor usage e.g. U.S., Germany have robust participation, whereas countries that block Tor pose barriers to access. Multilingual search is limited, users often rely on English keywords even when seeking non English hidden sites, which can bias what content is visible through these engines.

- Emerging Trends: AI assisted indexing is on the horizon experimental tools are exploring machine learning to summarize dark web forum discussions or identify relevant threat data automatically. Meanwhile, the community is considering decentralized search models peer to peer indexing to reduce reliance on any single search service that could be shut down. These trends aim to make hidden content discovery more resilient and intelligent, although they raise new accuracy and ethics questions.

In the shadows of the internet, dark web search engines serve as specialized guides to content that ordinary search engines like Google cannot reach. These tools index hidden websites on anonymous networks primarily the Tor network’s .onion sites and allow users, especially cybersecurity professionals, to query what’s happening in the underground. In 2025, dark web search engines are more crucial than ever. The dark web has swelled with activity, from bustling cybercrime bazaars to leak sites run by ransomware gangs. At the same time, navigating this hidden realm is dangerous without a map. Unlike the open web, where clicking the wrong Google result might get you a pop up ad at worst, clicking the wrong dark web link could infect your PC with malware or land you on illegal content.

This research based analysis examines the top dark web search engines of 2025 from a cybersecurity perspective. We’ll explain what these search platforms are and how they differ from normal search tools. We’ll analyze their capabilities, the kinds of content they cover, and how they’re used and misused by various actors. Crucially, we maintain a defensive lens: the goal is to understand these tools so organizations can monitor threats and researchers can investigate safely not to encourage illicit browsing. Real world events in 2025, such as major law enforcement operations and the evolution of dark web communities, have shaped the search landscape, we incorporate those developments to provide context on how these engines are used globally. In the end, we outline what these trends mean for defenders and list best practices for safe and ethical dark web research.

What Are Dark Web Search Engines?

Dark web search engines are specialized search tools for hidden services websites that reside on encrypted networks and aren’t indexed by standard search providers. Think of the internet as an iceberg: the surface web sites reachable via normal browsers and indexed on Google/Bing is just the tip. Beneath is the deep web databases, private intranets, etc., and deeper still is the dark web which requires anonymity networks like Tor The Onion Router or I2P Invisible Internet Project to access. Dark web sites use non guessable, cryptographic addresses such as 56 character .onion URLs for Tor v3 services instead of regular domain names. This design intentionally hides them from the indexing methods used on the clear web.

If the dark web is a secret library with unlisted books, then dark web search engines are like the custom card catalogs assembled by savvy librarians. They rely on Tor based web crawlers, link submissions, and user tips to find hidden sites. Unlike Google’s bots that can traverse billions of interlinked pages automatically, a dark web crawler faces a hostile environment:

- There’s no DNS or central directory of sites to start from. If a site’s onion address isn’t known or shared, a search engine can’t discover it just by crawling.

- Onion addresses are random looking and lengthy, derived from cryptographic keys e.g. juhanurmihxlp…onion. This means you can’t infer anything about the site from the URL, and brute forcing a new address is practically impossible due to the enormous address space.

- Many dark sites are ephemeral or deliberately unlinked. They may only exist for a few days on a popup scam site or a vendor’s page and aren’t linked to by others. A traditional search depends on links between sites, on the dark web, such link graphs are sparse and unreliable.

Because of these factors, dark web search engines only index a subset of content essentially, whatever they have managed to hear about and crawl. Each one’s index is a bit different. For example, Ahmia, a well known engine, uses a combination of crawling known onions and accepting user submissions of new site URLs. It also respects site owners’ requests not to be indexed via an opt in system similar to robots.txt to build trust with the community. On the other hand, an engine like Torch doesn’t wait for permission, it tries to crawl everything it can find, which results in a bigger index and more junk. Some services are more like curated directories than true search engines: they list categorized links e.g. The Hidden Wiki or DarkWebLinks instead of full text search.

From a defender’s perspective, dark web search engines matter because they transform the dark web from a totally uncharted maze into something at least partially navigable. Rather than manually scouring hacker forums or market sites for mention of your company’s data, you can use a search engine to quickly check if your company name, leaked email, or database appears on any indexed pages. They are essential OSINT tools for threat intelligence teams tracking criminal activity. However, these search engines are not foolproof or comprehensive. Many critical underground communities deliberately block crawlers or operate on invite only platforms that search engines can’t access. Thus, search results should be treated as starting points, not complete pictures.

To illustrate, consider an analyst investigating a new data breach: they suspect the stolen data might be for sale on the dark web. Using Ahmia or Haystak, they can search for the company’s name or domain and possibly find if an onion site is advertising the breach. This beats randomly trawling dark web forums. But the analyst must remain cautious the search engine might also list poisoned results phishing links pretending to be the breach. Good dark web search engines help minimize exposure to the worst content, but user vigilance is still the ultimate safety net.

Global Landscape of Dark Web Search

The use of dark web search engines in 2025 is a global phenomenon, paralleling the worldwide reach of the Tor network. Approximately 2 to 3 million people use Tor daily as of early 2025, and while not all of them use search engines, a significant portion of security researchers, journalists, and curious users rely on these tools to find information. There are a few key aspects to the global landscape:

- Accessibility: Technically, anyone with an internet connection and the Tor Browser can access dark web search engines, making them globally available. However, internet censorship in some countries affects usage. For instance, Tor is actively blocked or throttled in certain regions e.g. China, where the government has firewall rules against Tor traffic. In such places, users must use bridges or VPNs to reach Tor, which makes using dark web search engines more complex. By contrast, the United States, Europe, and many parts of Asia have large Tor user bases and relatively easy access, contributing to more active search behavior from those areas.

- Language and Regional Content: The major dark web search engines predominantly operate in English and index English language content. This is reflective of the common language used on many dark web forums and markets that cater to an international audience. However, regional differences exist. For example, Russian language darknet forums and marketplaces which are significant, especially in cybercrime may not be fully indexed by English centric engines. Some search platforms run by Russian users have existed or directories listing Russian onion sites, but they tend to be shared within those communities rather than globally advertised. The result is that an English query on Ahmia might surface lots of English forum posts about stolen credit cards, whereas a Russian speaking investigator might use other methods or communities to search Cyrillic content that isn’t well covered by Ahmia or Torch. Overall, multilingual support is limited, most dark web search engines lack the sophisticated language detection and translation features of Google. Users often must input queries in the language of the content they seek.

- Hosting and Availability: Dark web search engines themselves are hidden services onion sites, so their servers’ physical locations are obfuscated. Many also offer a clearnet web portal for convenience e.g., Ahmia provides a normal website ahmia.fi where you can search its index without Tor it will return onion links as results. This bridge allows global users to at least discover onion sites using a regular browser, then decide if they want to fire up Tor to actually visit them. Some other engines, like DarkSearch, similarly had a clearnet interface and an API to integrate into workflows. The presence of clearnet gateways means even users in corporate environments where Tor use might be flagged could query the dark web index through normal web ports though this comes with privacy trade offs the search service could potentially log queries.

- Regional Targeting and Use Cases: Different regions focus on different content niches. For example, European law enforcement and cybersecurity firms often use these search tools to track the sale of European citizen data or EU company breaches, given GDPR and other concerns. In North America, there’s heavy interest in drug markets and ransomware leak sites, which are actively searched to gather threat intelligence. Regions with higher cybercrime activities in certain domains e.g., Latin American financial fraud forums or Southeast Asian piracy hubs might have specific hidden sites that local investigators search for. Yet, the lack of regional customization in most dark web search engines means everyone is more or less searching the same combined soup of results.

- Visibility Trends: A notable trend is that whenever a big darknet market is busted or goes offline which often makes news globally, search queries from around the world spike for the name of that market or for alternative markets. For instance, after the Hydra market a huge Russian dark market was taken down in 2022, global interest in finding Hydra replacements surged, and engines like Torch were quick to index scam sites claiming to be the new Hydra. By 2025, the cycle had repeated with other markets. This indicates a global user reaction pattern: when familiar dark web sources disappear, users everywhere turn to search engines to find what’s next. The engines essentially become the beneficiaries of ecosystem volatility, seeing traffic boosts after raids or closures.

In summary, the global landscape for dark web search in 2025 is one where Tor’s reach is worldwide but unevenly used. The major search engines treat the dark web as a single global space, not split by country, which is useful for cross border threat intelligence. Criminals don’t respect national boundaries online. But regional factors, language, law enforcement pressure, censorship still influence how and how much these tools get used in different parts of the world.

Functional Capabilities & Coverage

Dark web search engines in 2025 can be compared by looking at their capabilities, the breadth/depth of their indexes, and the trade offs in using them. Instead of numeric metrics like index size which is often just an estimate, it’s more useful to compare qualitatively. The table below summarizes key capabilities across these platforms, with a note on the relative strength of each capability and associated risk level for users:

| Capability | Relative Strength | Risk Level | Notes |

| Indexing Depth & Breadth | High on uncensored engines Torch, Haystak indexing millions of pages. Moderate on filtered engines Ahmia, Not Evil smaller, curated index. | Content Risk: Higher on broad indexes more likely to include malicious or illicit content. | Unfiltered engines maximize coverage, useful for finding obscure references. However, they include all the junk and harmful sites. Filtered engines deliberately miss some content e.g., anything flagged illegal, trading completeness for safety. |

| Content Filtering/Safety | Strong on Ahmia, Not Evil active blocking of known abuse material. None/Low on Torch, OnionLand little to no filtering. Users driven on Not Evil community flags remove bad sites. | Legal/Exposure Risk: High on unfiltered engines users may encounter CSAM or scams, Low on filtered less likely to see dangerous content. | Ahmia maintains a blacklist e.g., for CSAM. Not Evil relies on users to report illicit sites, which are then removed. Engines like Torch index everything the user must self filter results. High risk of stumbling on illegal material with uncensored results, requiring extreme caution. |

| Search Features & Filters | Advanced on Haystak premium regex, phrase search, historical cache. Basic on most free engines simple keyword search, some support exact quotes. APIs on DarkSearch and others for programmatic querying. | OPSEC Risk: Moderate if using advanced features requiring accounts or contact e.g., premium sign up could expose identity if not careful. | Haystak’s paid tier offers powerful filtering date ranges, exact matches and a cache of pages even if the site is offline valuable for investigators. DarkSearch provided a free API so security tools can integrate dark web queries. Basic engines lack these refinements, meaning more manual effort. Using any account based feature, even just an email for alerts, introduces slight deanonymization risk, so users should use burner identities. |

| Update Frequency | Frequent on large engines Torch/Haystak actively crawl, though dark web sites often die fast. Manual/Slow on curated ones Ahmia updates when new links found or submitted. Dead Link Pruning on some Ahmia and others periodically remove defunct sites. | Accuracy Risk: Medium high churn means results can be outdated or links dead. | Because many onion sites have short lifespans, an engine might list a site that’s no longer accessible. Engines with health checks will label or drop those. Haystak claims a huge index but that can include many dead pages. Users often must try multiple search engines if one returns too many outdated results. |

| Accessibility Tor vs. Web | Dual access for engines like Ahmia Tor service + clearnet site and DarkSearch Tor + web. Tor only for others Torch is onion only, Not Evil onion only. Some engines require JavaScript enabled OnionLand’s modern interface, others work in no script mode Ahmia, Torch, etc.. | Privacy Risk: Using clearnet portals can expose search queries to the open internet engine may log IP unless using VPN. Enabling JS on Tor is highly risky and could reveal identity via exploits. | Clearnet access is convenient for initial searches and faster, but should be done carefully using VPN or at least not search sensitive personal info on a public site. When using Tor, sticking to no script is safest, any engine that forces JavaScript e.g., for fancy features or captchas raises the risk of browser deanonymization. Users should prefer text based interfaces when possible for maximum safety. |

| Network Coverage | Tor focused on nearly all indexing .onion v3 sites. Multi network on a few OnionLand also indexes some I2P eepsites and even clearnet proxies. I2P dedicated search exists e.g., Legwork for I2P but with much smaller reach. | Accessibility Risk: Low not a risk to user, but multi network results might be confusing or less useful e.g., I2P links if user isn’t on I2P. | Virtually all top search engines concentrate on Tor. OnionLand stands out by attempting to unify results from Tor and I2P, but this is an experimental feature, many I2P sites still won’t be found easily. For most users and threat hunters, Tor search is the priority since that’s where the bulk of dark web content resides. |

No single dark web search engine is best on all fronts, there’s a trade off between comprehensiveness and safety. A prudent strategy is to start with a safe, filtered engine to get initial results with lower risk and then, if needed, use an unfiltered engine to expand the search, all while following strict OPSEC practices. The capabilities also suggest that serious investigators might use multiple tools: for example, query Ahmia for a quick, safe look, then use Haystak’s advanced features or API for deep dives, and perhaps OnionLand if they suspect something might be on I2P.

Common Use Cases Observed Defensive Context

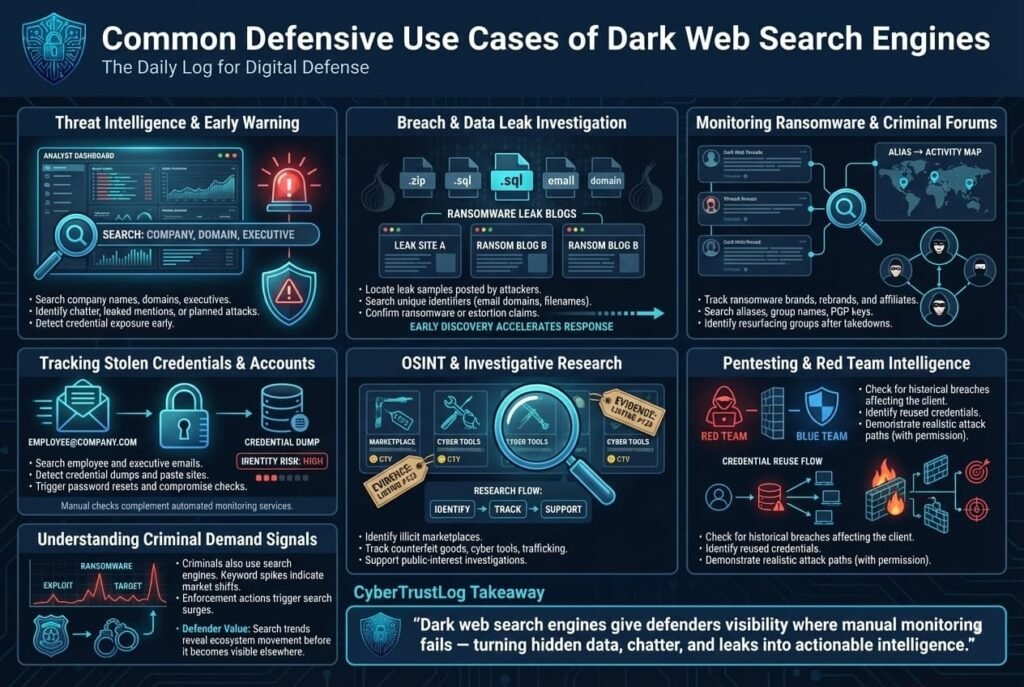

Dark web search engines are invaluable for various defensive and investigative use cases. Below we outline how cybersecurity professionals and researchers commonly leverage these tools in 2025:

- Threat Intelligence Gathering: Teams in Security Operations Centers SOCs and threat intelligence units use dark web search to uncover early warning signs of attacks. For instance, searching for the organization’s name, domain names, or key personnel on engines like Ahmia can reveal if hackers are discussing the company on forums or if stolen data mentioning the company is up for sale]. If a search turns up an employee email and password on a paste site indexed on the dark web, it can indicate a credential leak that warrants a forced password reset and further investigation. Similarly, banks and financial institutions search for BIN numbers or card dumps related to them, healthcare organizations search for mentions of their patient databases all to catch criminal activity involving their assets.

- Breach and Data Leak Investigation: When a data breach is suspected or confirmed, dark web search engines help find evidence of the stolen data. Often, after a breach, criminals post samples of data on Tor sites to prove legitimacy for ransom or sale. By querying unique strings from the leaked data like a specific email domain or file name, analysts can locate these leak posts. This was traditionally done by manually combing through known leak sites, but engines like Haystak now crawl many ransomware leak blogs and make them searchable including historical caches for sites that are taken down. Investigators use this to quickly confirm if a given threat actor has mentioned their company. It’s a race catching a leak early and can aid incident response and customer notifications.

- Monitoring of Ransomware and Criminal Forums: Ransomware gangs and other threat groups often operate sites on the dark web where they announce victims or chat on forums. Continuous monitoring via search engines can alert defenders to new developments. For example, if LockBit, a ransomware gang, launches a new version or rebrand, security researchers will search for LockBit 3.0 or related terms to find any hidden posts or sites discussing it. In 2025, with the takedown of certain ransomware affiliates, search engines were used to find where those groups resurfaced. Some specialized search services even scrape these forums and let you search by alias or PGP key. While public search engines might not index every invite only forum, they do index many public dump sites and older forums, making them a starting point to track threat actor activity.

- Tracking Stolen Credentials and Accounts: A huge portion of dark web activity involves stolen login credentials, emails, usernames, passwords. Organizations integrate dark web search in their threat hunting to find if any employee or customer credentials have leaked. For instance, typing an executive’s corporate email into a dark web search engine might show it appearing in a credential dump listing. There are commercial services that do this at scale, but analysts can replicate some checks manually. If a hit is found e.g. user@company.com password123 on a known breached data repository indexed by the engine, the team can initiate remediation to ensure the password is changed, check for related compromise. Notably, Google launched a Dark Web Report to notify users of such appearances, but that service is ending in 2026, putting more onus on security teams to directly monitor for exposed credentials.

- Open Source Intelligence OSINT Research: Journalists, academic researchers, and OSINT investigators also use these engines for legitimate investigations like uncovering illicit trafficking networks or gathering evidence of cybercriminal marketplaces. For example, an OSINT analyst investigating counterfeit pharmaceutical sales might search dark web engines for specific drug names or vaccine batches to find sellers. Researchers mapping the supply chain of a cyber weapon might use search engines to discover related advertisements or tool names on hacker boards. These use cases serve the public interest exposing criminal operations, supporting law enforcement with leads, and the search engines act as force multipliers, saving countless hours by aggregating data that would otherwise require accessing numerous sites individually.

- Pentesting and Red Team Operations: Interestingly, even some offensive security professionals the good guys conducting authorized hacks use dark web searches during engagements. In a penetration test, testers often check if their client has any prior compromises revealed online. If a pentester finds employee credentials in a 2023 database leak via a dark web search, they can use that intelligence to demonstrate a threat: try those credentials on the client’s systems with permission to show a potential breach path. This ties back to threat intelligence, but in a very tactical, immediate way. Red teams mimic attackers and real attackers often leverage dark web data so the red teams do so as well, via these search tools.

It’s important to stress: all these use cases are about defense, prevention, and investigation. Direct criminal use of search engines like a buyer using Torch to find a new drug vendor certainly happens as well. That’s partly why engines like Torch remain popular in the underground, since they help customers find illicit products after marketplaces get busted. However, from a security standpoint, understanding even that use case has value: e.g., law enforcement might monitor search trends for certain keywords to anticipate where the market is moving next. If searches for fentanyl spike in a certain engine, it might indicate new vendors or demand patterns.

In summary, dark web search engines are versatile tools for defenders. They surface hidden threats whether that’s leaked data, criminal chatter, or malicious services enabling proactive measures. Without them, analysts would be largely blind in the dark web’s depths or forced to manually track hundreds of sources. With them, a single query can shed light on a previously unknown risk. The cost, of course, is that one must use them carefully and ethically, given the minefield of illicit material present on the dark web.

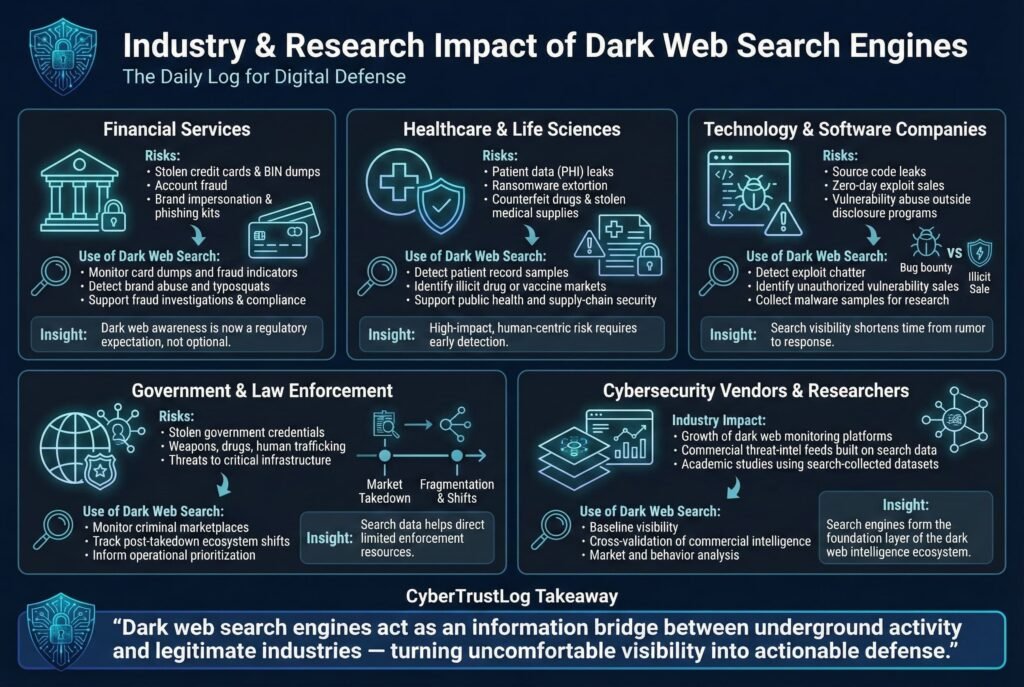

Industry & Research Impact

The presence and evolution of dark web search engines have significant implications across various industries and the cybersecurity research community. Below we discuss their impact on a few key sectors and contexts:

- Financial Services: Banks, payment processors, and insurance companies are heavily targeted on the dark web for stolen financial data. The industry has responded by incorporating dark web monitoring often powered by these search engines or their backend data into fraud detection and compliance. For example, credit card issuers keep tabs on card dumps and BIN numbers being sold, a sudden influx of cards from Bank X showing up in search results might indicate a point of sale breach at a merchant, prompting an investigation. Moreover, financial firms worry about brand abuse on the dark web phishing kits imitating their login pages. By searching for their brand names or typosquats on dark web engines, they can find phishing templates or discussions of attacks targeting their customers. This intelligence feeds into risk assessments and sometimes law enforcement referrals. Industry wide, the use of dark web data sourced via search or commercial feeds has become a standard component of fraud risk management so much so that regulators in some regions expect banks to demonstrate they are aware of relevant dark web threats e.g., if thousands of their customers’ records are on a darknet forum and they missed it, it looks bad.

- Healthcare: Hospitals and healthcare providers have seen a surge in ransomware and data theft, with patient data being peddled online. Dark web search engines are used by healthcare security teams to check for PHI Protected Health Information leaks. If an engine indexes a dump of patient records which might happen if a ransomware gang posts a sample to pressure the hospital, the hospital can quickly identify it and work with authorities. The ethical stakes are high: patient data leaks can be life threatening, considering doxxing of patients, or exposure of HIV statuses, etc.. Therefore, healthcare organizations often subscribe to threat intel services that leverage these search tools to continually watch for their data. Researchers in healthcare cybersecurity also study dark web markets for things like counterfeit medicines or vaccines using search engines to find those illicit vendors. The insights gained can inform public health responses and medical supply chain security for example, detecting a batch of stolen oncology drugs being sold illegally.

- Technology & Software Companies: These companies worry about intellectual property leaks, source code, proprietary algorithms and zero day exploits being discussed on the dark web. Security researchers in this sector use search engines to find chatter about vulnerabilities in their products on hacker forums. For instance, if someone claims to be selling an exploit for a popular software, a dark web search might surface that listing. Tech firms then can initiate their incident response either trying to purchase the exploit via law enforcement or patching it if details are gleaned. Also, big tech companies often have bug bounty programs, and occasionally disgruntled researchers or criminals will try to sell vulnerabilities on the dark web instead of disclosing. Keeping an eye via search can catch these. On the flip side, some tech companies like antivirus firms use these engines to gather malware samples by finding sites hosting malware to improve their products. The research impact is evident: academic studies of cybercrime frequently rely on data collected through these search engines, because it’s one of the few systematic ways to get info about multiple forums/markets at once.

- Government and Law Enforcement: Government cybersecurity teams for example, those protecting critical infrastructure or doing counterintelligence leverage dark web search to identify threats to public safety. This can range from finding stolen government credentials, diplomatic emails, military login passwords to monitoring for extremist activity. Although terrorist content tends to be on the deep web or private channels more than Tor, law enforcement does search Tor for things like weapon sales or human trafficking ads. The public sector also studies the dark web economy at large to inform policy. For instance, agencies like the FBI or Europol have units that analyze marketplace trends, volume of opioid sales, etc., and some of that data comes from scraping and searching dark web markets. As a concrete example, Operation RapTor in 2025 a global darknet drug crackdown didn’t end the online drug trade, within months, dozens of smaller shops emerged. Government analysts watched this happen partly by seeing the spikes in search engine activity for those drug terms, which helped them prioritize new investigation targets]. The intelligence gathered through search engines thus shapes where resources are deployed next. In another aspect, the research arms of defense organizations examine dark web tools for vulnerabilities e.g. figuring out how to deanonymize services. To do that, they often start by using search engines to map out the landscape of hidden services to target.

- Cybersecurity Vendors and Researchers: A whole sub industry has blossomed around dark web monitoring services offered by companies like Recorded Future, DarkOwl, Kela, etc.. These services often present themselves as more advanced than simple search engines, but under the hood many are essentially enhanced dark web search engines with bigger indexes, proprietary collections, and analytics on top. They feed on the same ecosystem. The availability of free search engines like Ahmia or Torch provides a baseline, but vendors differentiate by having longer historical data, better filtering, and linking identities across sites. Researchers benefit because they can validate findings an open search engine hit can be cross checked with a commercial feed for confidence. Additionally, academic researchers use data from engines to conduct studies like measuring what percentage of results are illicit, or analyzing search query patterns to see what’s in demand on the dark web. Notably, one study of Ahmia’s search logs found a significant fraction of queries were explicitly seeking illegal material, highlighting that a portion of users do attempt to find harmful content, which in turn justifies the continued need for filtering by responsible platforms.

In essence, dark web search engines act as an information bridge between the underworld and legitimate industries. The impact is largely positive for defenders: improved visibility leads to more proactive defense. But it also means that industries have to confront uncomfortable truths e.g., seeing your company’s customer data show up in a Torch result is alarming, but it’s better to know and respond than to remain ignorant. By 2025, using these tools directly or via a vendor is considered a best practice in many sectors for maintaining cyber situational awareness.

Regional Considerations

While our discussion is global, certain regional considerations affect how dark web search engines are perceived and used:

- Legal Exposure and Jurisdiction: Different countries have different laws about accessing dark web content. Generally, using a dark web search engine and viewing content is not illegal in most jurisdictions, illegality usually comes from participating in crimes or downloading/distributing illicit material. However, some countries have broad cybercrime laws where even accessing certain content like extremist materials is a gray area. For example, in some Middle Eastern or Asian countries, just accessing the dark web is itself seen as suspicious. Researchers in those regions must be extra careful, possibly doing all work through anonymizing services and ensuring no illegal content is stored on their devices which could be a crime to possess. In contrast, Western countries allow dark web research but still enforce laws on content e.g., if you intentionally download illegal pornography from a hidden site, the fact it was on Tor doesn’t protect you from prosecution. So regionally, the appetite for dark web monitoring can depend on legal comfort. European companies often consult legal counsel for guidance on how to handle discovered data like if they find personal data of EU citizens via a search engine, GDPR might even consider viewing that as processing personal data requiring a lawful basis. Thus, European defenders tend to have processes to document why they are collecting dark web info for fraud prevention, etc., which is usually permissible.

- Law Enforcement Intensity: In the U.S. and EU, law enforcement has dedicated significant resources to dark web operations FBI’s J CODE, Europol’s dark web team, etc.. They sometimes take over or impersonate dark web sites and could potentially run or monitor search services too. There have been rumors in the community about certain search engines possibly being fed data by law enforcement to track who searches for what though no firm evidence of this for the major ones. However, users in authoritarian countries have a different fear: their governments might monitor Tor usage as a flag for dissidents. For instance, in countries like China or Iran, if one were able to use a dark web search engine, that alone might draw unwanted attention. Regionally, this results in different operational security postures: A human rights researcher in a repressive regime must take steps to hide the mere fact that they are using Tor bridges, VPN over Tor so as not to endanger themselves. Meanwhile, a European threat intel analyst is more concerned about not breaking laws inadvertently than about government surveillance of their searches.

- Monitoring Maturity: Regions with mature cybersecurity industries North America, Europe, parts of APAC have more organizations actively monitoring the dark web as part of their routine. In these regions, there’s also a market for training and certifications around dark web investigations, which emphasize using search engines effectively. In contrast, in developing countries or smaller markets, companies might not yet include dark web checks in their security practice. They might rely on third party services or not at all. This means threat actors sometimes exploit those gaps for example, criminals might specifically target companies in regions where they suspect cybersecurity is nascent, figuring those companies won’t be watching the dark web to notice the intrusion or the sale of their data. Over time, this is changing, with even banks in Africa or South America starting to use dark web monitoring, often driven by regulations from global partners.

- Cultural Perception: In some regions, the dark web is highly stigmatized or mythologized, which can affect willingness to engage. A company in a conservative industry might hesitate to let employees use a dark web search engine even for security, out of fear of what if something goes wrong. On the flip side, countries with a strong privacy culture like Germany produce tools like Tor Browser and support things like Ahmia’s development. Finland, for instance, is where Ahmia originated with backing from the Tor Project showing regional support for privacy aligned search. Russian cybercrime forums historically didn’t need search engines because they were closed communities, but interestingly, when those forums want to attract international buyers, they ensure their sites get indexed by engines like Torch. Thus, criminals adapt regionally too if they want a global audience, they’ll embrace being found via search.

In summary, the core technology of dark web search engines is region agnostic, but how they’re used, monitored, and regulated has regional nuances. Defenders must be aware of their local laws and threat landscape when integrating these tools into their strategy. For most, the advice is: proceed, but with caution and clear policy guidelines.

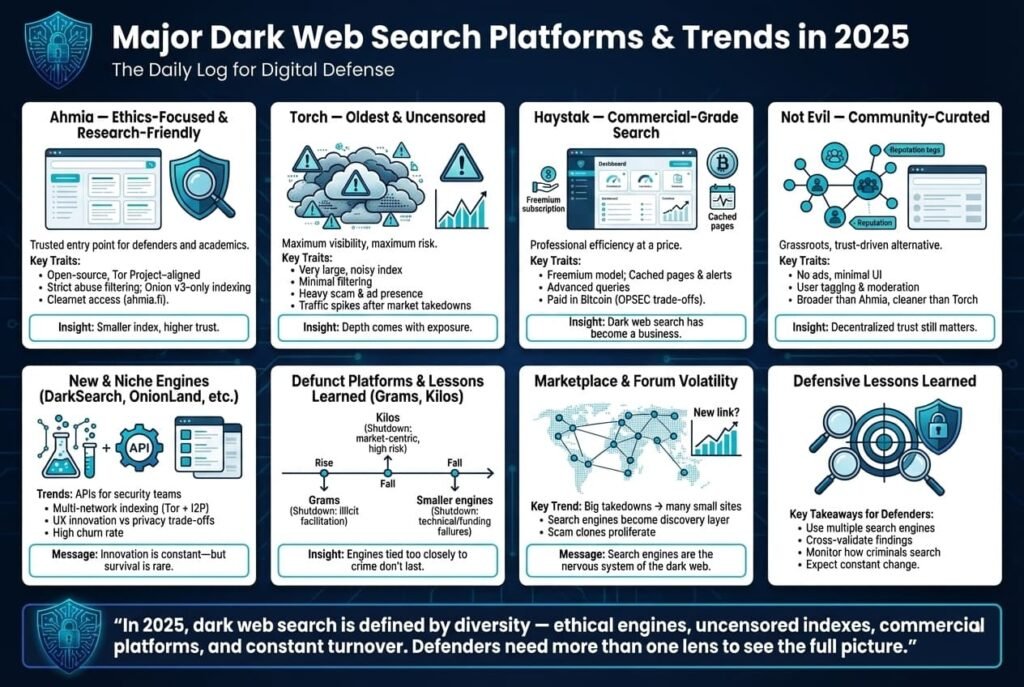

Major Platforms and Trends in 2025

By 2025, several major dark web search platforms have solidified their presence, each with its own philosophy and user base. Additionally, the ecosystem has experienced notable shifts due to site shutdowns, new entrants, and law enforcement pressure. Here we outline the notable platforms and patterns:

- Ahmia The Ethics Focused Engine: Ahmia remains one of the top recommendations for newcomers and researchers who want a clean dark web search experience. It’s backed by the Tor Project and has been around since the mid 2010s. Ahmia’s significance in 2025 lies in its consistent stance on transparency and safety: it is open source, has a public abuse list, and clearly communicates that it filters out harmful content e.g. it will not show results for child abuse sites, etc.. This approach has made it a trusted starting point, especially in academic and corporate circles. Ahmia’s clearnet portal ahmia.fi also makes it easily accessible for quick searches. Its limitation as a smaller index has become more apparent as the dark web expanded, but for 90% of use cases like finding known leak sites or major forums, it suffices. In 2025, Ahmia also continued to index onion v3 addresses exclusively v2 addresses were deprecated and are largely gone by now, which improved security but required re-seeding its index when Tor made that transition. Ahmia’s presence underscores a trend: a push towards making the dark web accessible without accidentally seeing the worst of humanity.

- Torch The Oldest Uncensored Index: Torch is often nicknamed the Google of the dark web at least in terms of age and index size and by 2025 it has indexed millions of pages over its long existence. It stands out for its longevity, it’s been operational since at least the late 2000s and for its anything goes approach. In 2025, Torch’s results are still peppered with dubious links and scam ads, which is both a blessing and a curse. On one hand, if something exists on the dark web, Torch likely has a record of it, making it invaluable for exhaustive searches. On the other hand, using Torch requires a strong stomach and strong security: one might find a whistleblower site… but right next to it results in a link to malware or graphic content. Torch hasn’t significantly innovated, its interface is basic, even outdated, full of banner ads for cryptocurrency tumblers or shady services. Yet, its resilience to takedown and sheer volume of content reflect a key pattern: uncensored engines maintain popularity for deep access despite the risks. Many experienced dark web users accept Torch’s noise because when you need that one obscure piece of info, Torch often delivers. In 2025, Torch also benefited from marketplace crackdowns: when big markets fell, Torch’s traffic spiked as displaced users searched for new markets or alternatives e.g., searches for marketplace name+new link. This showed Torch’s role as the go to for the community when official link directories often hosted by the markets themselves on forums were in flux.

- Haystak The Commercial Grade Search: Haystak has grown into the largest dark web index by some claims, boasting an index of over 1.5 billion pages. Whether that number is current or marketing hype, by 2025 Haystak is notable for introducing a freemium model on the dark web. Its free version gives basic search functionality similar to others. Its premium tier, however, offers features attractive to professional investigators: cached page views so even if a site disappears you can see what was there, advanced query syntax, and email alerts for specific keywords. This marked a shift in the dark web ecosystem commercialization and professionalization. Notably, Haystak’s premium isn’t cheap and is paid in Bitcoin. This raised interesting OPSEC questions: paying for a dark web service links an identity, a Bitcoin address or transaction to usage of that service. Savvy users will tumble/mix their coins to avoid traceability, but it adds friction. Despite that, by 2025 many threat intel firms and journalists had Haystak subscriptions, as the efficiency gains outweighed concerns. Haystak also has a relatively clean UI and no ads for premium users, making it feel like an enterprise product. The lesson learned is that as the dark web became big business for criminals, the tools to police it also became a business. Haystak’s success might inspire similar models, imagine a premium I2P search, or a subscription based darknet data API. It also underscores that even on the dark web, people will pay for convenience and quality data.

- Not Evil The Community Curated Search: Not Evil a play on Google’s old motto Don’t be evil is a non profit search engine that in 2025 still operates with a very minimal design and no ads. Its unique aspect is community policing: users can actively tag or report sites in the results as scams, spam, or worse, and the index updates accordingly. The result is a cleaner index than an unfiltered one, without a single authority deciding what to exclude aside from blatant abuse, presumably. Not Evil’s relevance in 2025 is somewhat niche, it’s favored by more technically inclined users and those who are ideologically opposed to profiting from darknet search. It had periods of downtime and might not be as comprehensive as Torch or Haystak. However, its survival indicates a continued demand for grassroots, open darknet tools. Historically, a predecessor called TorSearch was shut down around 2014 the developer voluntarily took it offline after some FBI concern, if memory serves, but Not Evil rose later using a different approach. By 2025, it’s essentially an established player, often listed among top dark web engines, and serves as a good middle ground: broader than Ahmia since it doesn’t filter as strictly, but with less toxic content than Torch thanks to user moderation. The trend here is the reliance on community trust, something that fits the decentralized ethos of the dark web.

- DarkSearch, OnionLand, etc. Newer and Niche Engines: Aside from the big names, there are always emerging search engines. DarkSearch, not to be confused with a similarly named darksearch.io service came onto the scene offering an API and branding itself as by security pros, for security pros. It tried to cater to corporate users with integration in mind. OnionLand positioned itself as a modern search that even indexes I2P sites and provides a Google like experience with search suggestions and possibly richer results. However, OnionLand requires JavaScript to use effectively, which has made privacy conscious users wary since enabling scripts on Tor is risky. These newer engines illustrate a pattern of experimentation: some focus on better UI/UX, some on multi network search, others on specific content verticals e.g., there was an engine focused on dark web marketplaces specifically, another on paste sites. Not all survive, some disappear due to lack of funding or low traffic, others potentially due to being scams or law enforcement targets.

- Defunct or Deprecated Engines: It’s instructive to note which search engines didn’t survive to 2025. One famous example is Grams, launched in 2014 as the first Google for dark web markets. It was quite successful including features like Grams Helix bitcoin mixer, but it shut down in 2017 when its operator decided to exit later it came to light the operator was arrested for the Helix tumbler aspect. Grams’ shutdown left a void that engines like Kilos aimed to fill. Kilos, launched in late 2019, was explicitly geared toward searching multiple markets and forums for products catering to buyers after big markets fell. It mimicked Google’s design and introduced features like filtering by price or market, essentially servicing criminal users more than researchers. Kilos rose to prominence around 2020 but, by 2025, its status is a bit ambiguous, it’s mentioned in some top engines lists, implying it might still be accessible. If it’s around, it’s likely operating more quietly, given increased law enforcement scrutiny on anything market related. Another one was DeepSearch, an open source engine focusing on precise results and spam filtering. If it’s the same DeepSearch as referenced in some 2026 lists, it suggests a continued interest in quality over quantity indexing. Meanwhile, many smaller search sites or link lists have come and gone like TorLinks directories that got outdated or Recon, an engine for vendor profiles that was associated with a marketplace and fluctuated with it. Each defunct engine often teaches a lesson: Grams showed that too much entanglement with illicit facilitation the mixer invites shutdown, Kilos showed that explicitly catering to drug buyers is risky, others simply couldn’t keep up with the technical challenges or costs.

- Marketplace and Forum Shifts: 2025 saw events like Operation RapTor global drug market bust and continued targeting of ransomware gangs. These caused decentralization instead of a few big marketplaces, we got many small ones. Dark web search engines thus became more important to find these smaller sites. A user who previously only needed the Hidden Wiki to find a big market now might have to search for brandname fentanyl shop to discover a small vendor’s site. This shift reinforces that search engines are the nervous system of the dark web: when the body of the markets loses a part, the system rewires through search. Also, forums like Dread a Reddit like darknet forum often go down or change domains due to DDoS or admin issues when that happens, users search for Dread new link and engines serve up the answer though often scammers create fake Dread links to trap users, which again are indexed so caution is needed.

Defensive Lessons Learned: for cybersecurity defenders, one major lesson from these platform shifts is the need to stay agile with multiple tools. If you relied only on one search engine and it goes down or its index becomes stale, you could miss critical intel. For example, if an investigator only used Ahmia, they might miss content that Ahmia filters out so they learned to double check on a broader engine like Haystak or Torch. Another lesson is to pay attention to the dark web community’s own use of search: when criminals start using specialized engines like Kilos to find stuff, that indicates the surface web is truly inadequate for them meaning more activity is siloed in the dark web. That, in turn, hints that defenders need to be present there via their tools, since the threats won’t spill out to Google as obviously.

In summary, the 2025 landscape of dark web search is characterized by a mix of legacy stalwarts Ahmia, Torch, innovative newcomers Haystak’s model, OnionLand’s multi net search, and the ghosts of past platforms that shaped today’s approaches Grams, etc.. The ecosystem is dynamic when one engine falls, another often takes its place, reflecting the resilience of both the dark web and efforts to index it. For defenders, using these platforms wisely is akin to using different lenses to get the full picture of the underground.

Emerging Trends in Dark Web Search

Looking forward from 2025 into 2026 and beyond, several emerging trends are poised to influence dark web search engines and how we use them:

- AI Assisted Dark Web Analysis: Artificial intelligence AI, particularly natural language processing and machine learning, is increasingly being explored to make sense of dark web content. While current search engines stick to keyword matching and simple filters, next gen platforms may integrate AI to summarize and contextualize dark web data. Imagine querying not just a keyword, but asking a question: What are hackers saying about Windows 11 vulnerabilities this month? An AI powered system could attempt to aggregate discussions from multiple forums and give an answer. Some experimental tools and research projects are heading this way, training language models on dark web text with all appropriate caution. The benefit for defenders is huge: it could surface insights, trends, sentiments, and common tactics that a basic search would leave buried under thousands of posts. However, there are challenges: AI might hallucinate or misidentify context on the dark web, and there’s the ethical matter of letting an AI read through extremely toxic content which could influence its outputs. Still, we anticipate more smart search features, such as clustering of results e.g., if you search a company name, the engine might cluster results into credentials leaks, mentions on forums, listings on markets using AI to categorize. Some threat intel companies are likely already prototyping these capabilities.

- Decentralized and Resilient Search Networks: A counter movement to big centralized indexes is the idea of peer to peer search networks on the dark web. Given that centralized sites are takedown targets either by law enforcement or DDoS by criminals, a decentralized search would store pieces of the index across many nodes perhaps even on users’ machines. Projects like YaCy, a P2P search engine for the clearnet, could be adapted for Tor/I2P usage. In such a model, no single entity owns the search index, making it censorship resistant. If done right, it could also alleviate the trust issue of central server logging queries. We haven’t seen a popular decentralized dark web search yet, but interest is growing as privacy advocates and censorship resistance proponents push the envelope. The trend aligns with the broader ethos of decentralization e.g., cryptocurrency like thinking applied to search. The challenge will be efficiency and security: distributing a dark web index means every participant might hold references to illegal content, which raises legal questions, and performance might lag behind a tuned central service. Nonetheless, this trend could produce at least experimental tools that defenders might use as a backup if major engines go offline.

- Integration with Mainstream Tools: We might see dark web search capabilities more tightly integrated into mainstream security tools. For instance, SIEM Security Information and Event Management systems or threat intelligence platforms could have built in dark web search modules, so that an analyst in Splunk or Microsoft Sentinel can right click an indicator like an email or IP and search a dark web index without leaving their console. Some products already do this via API connections to engines like DarkSearch or via data from dark web monitoring companies. The trend is the blending of dark web intel into everyday cybersecurity workflows. This way, checking the dark web for context becomes as normal as checking VirusTotal for a malware hash. The barrier between surface web analysis and dark web analysis will likely shrink, driven by the increasing recognition that many threats germinate on the dark web.

- Greater Law Enforcement Scrutiny and Interference: Future dark web search engines might have to contend with more active interference. It’s not unthinkable that agencies could deploy fake content to dark web sites as sting operations that also gets indexed, or that they could subpoena or compromise search services especially those with clearnet presence to get data on who is searching for what. In fact, Google’s withdrawal from offering a consumer dark web monitoring tool hints that this domain is moving out of the mainstream tech companies’ hands and into the purview of specialized firms and government watchers. By 2026, if you’re using a dark web search engine, you should assume that your queries might be of interest to someone. This isn’t a reason not to use them but expect to see more overt warnings, disclaimers, and even partnerships between search engines and law enforcement when it comes to extreme content for example, an engine might display a banner like Searches for child abuse content will be reported such a measure would be controversial in the privacy community, but as AI could detect such queries, it may become a debate.

- Shifts in Dark Web Architecture Affecting Search: Tor itself is evolving. For instance, proposals to make onion services more scalable or to incorporate anonymous searchable tags in site descriptors have been floated by researchers. If any such feature were added even experimentally, it could allow search engines new ways to discover hidden services. Also, the growth of alternatives like ZeroNet, Lokinet, and others if they gain traction might broaden what dark web search means beyond Tor and I2P. In 2025, Tor is king, I2P is second far behind, others are negligible. But tech landscapes can shift. If, say, a decentralized social media over Tor/I2P emerges and becomes popular, search engines would need to index those posts much like how search engines eventually needed to index social media content on the clearnet.

- User Experience Improvements: A minor but notable trend is making dark web search more user friendly without compromising safety. For example, engines could implement on the fly URL validation warning users if an onion link they clicked is known to host malware, kind of like how browsers warn of phishing sites. Some engines might integrate translation services so you can search in one language and get results from another. Imagine typing in English and finding Russian forum posts with an automatic translation snippet, currently one has to copy and paste into translators manually. Another UX trend is mobile friendly access with more people capable of running Tor on mobile, there might be efforts to make search engine sites render well on mobile Tor Browser, acknowledging that not all threat intel browsing is from a PC.

Overall, the emerging trends point towards a smarter, more integrated, but also more contested dark web search environment. For defenders, the use of AI and better integration will be positives, making it easier to glean insights. But the continual cat and mouse between privacy, criminal use, and law enforcement will shape how freely these tools evolve. One thing likely remains true: the dark web isn’t going away, and neither is the need to index and search it for the sake of security and knowledge.

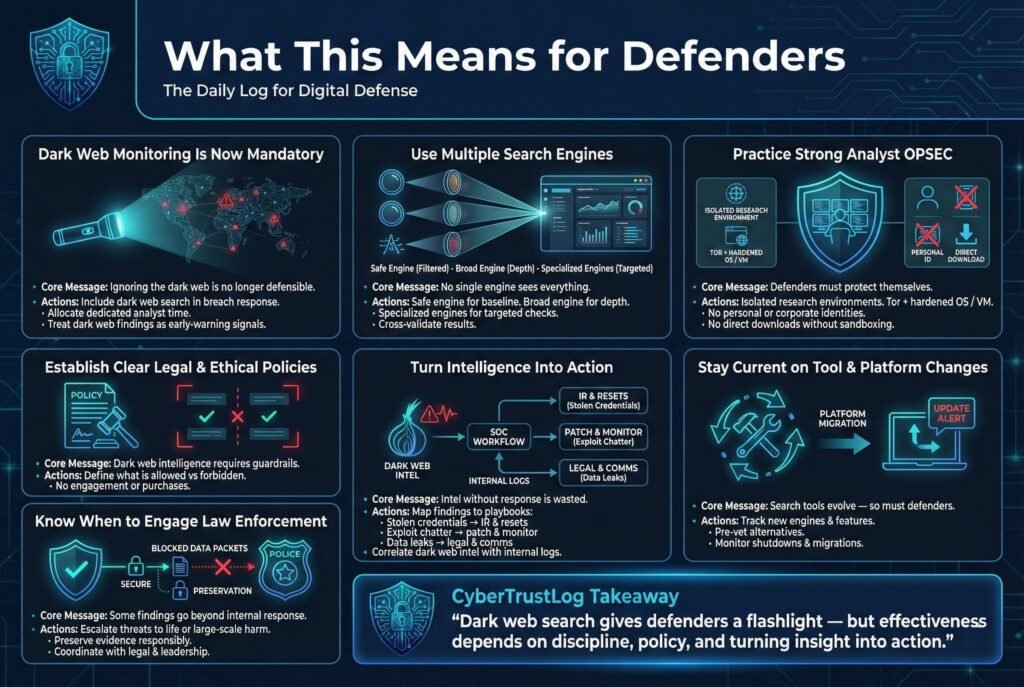

What This Means for Defenders

For cybersecurity defenders and professionals, the evolution of dark web search engines carries several implications:

1. Dark Web Monitoring is Indispensable: If it wasn’t already clear, by 2025 it’s evident that no serious security program can afford to ignore the dark web. Breach data, threat actor plans, and indicators of compromise often surface there first. The refinement of search engines means that defenders have the tools at their disposal to peek into these hidden forums and markets. Therefore, defenders should formally incorporate dark web search into their threat intelligence and incident response processes. For example, for every confirmed data breach, a procedure should include searching the dark web for leaked data or mentions as a step. Security leadership should allocate time and resources, maybe a dedicated analyst role for dark web reconnaissance using these engines. The intelligence gathered can directly reduce harm e.g., spotting an attack being discussed could allow preemptive defenses, identifying leaked accounts can prompt password resets before they’re used maliciously.

2. Multi Engine Approach for Coverage: As highlighted, each search engine has blind spots. Defenders should avoid relying on only one source. A combination strategy works best: use a safe engine Ahmia for initial scans, a broad one Torch or Haystak for exhaustive searches, and maybe specialized ones like a breach data search engine or a marketplace specific one for particular tasks. By cross referencing results from multiple engines, defenders can be more confident in their findings. This also helps filter false positives if only one engine shows a result and others don’t, maybe that result is outdated or dubious. Essentially, think of it like threat intel fusion: merge data from various dark web search feeds to get a robust picture. Organizations might even develop an internal dashboard that pulls from a few dark web sources so analysts can search once and get aggregated results.

3. Enhanced OPSEC for Analysts: Defenders must practice what they preach in terms of security when they themselves venture onto the dark web. Using these search engines should be done in a dedicated secure environment e.g., a non Windows machine to reduce common malware impact running Tails or a hardened Linux, inside a VM perhaps, and only over the Tor network possibly coupled with a VPN for extra cover. Analysts should never use their personal or corporate identity on these networks. This means never logging into any dark web site with an email or username that links back to the company. Also, policies should forbid downloading files from dark web results unless through secure sandboxing a seemingly benign PDF from a leaked dataset could be booby trapped. Another OPSEC aspect: be mindful of search terms. Searching very unique terms like an extremely specific filename from your internal system on a public engine could theoretically tip off an observer that your organization is looking into that issue. Most likely this is a minor risk, but savvy defenders sometimes add a layer of obfuscation: e.g., searching a slightly more generic term first to find the right page, rather than a fingerprint that screams Company X confidential file.

4. Clear Policies and Legal Guidance: Defending via dark web intel walks an ethical and legal tightrope. Companies should have clear guidelines on what analysts are allowed to do. For instance, viewing pages is one thing, but interacting like trying to purchase data to verify it crosses into dangerous territory legally. Typically, the rule is to never engage or give money to criminals, even if just to confirm a breach leave that to law enforcement. Also, if an analyst inadvertently encounters illegal material, say an image of exploitation, there should be a procedure: do not copy or distribute it, report it to legal/authorities as required, and scrub it. Having these policies written and training given is crucial so that analysts don’t make ad hoc judgment calls that could land in hot water. Another policy aspect is data handling. If you find a database of user records, do you download it for analysis? That might be illegal in some jurisdictions unless law enforcement is involved. Often, just documenting the URL and a snippet is enough, then involve legal teams.

5. Leverage Intelligence to Drive Defense: It’s not enough to gather dark web information defenders need to operationalize it. That means integrating it into risk assessments, patch management, and user protection. For example, suppose a search engine reveals that a new exploit kit is being sold targeting a certain VPN appliance, the defenders should treat that as an urgent warning even if their own systems aren’t yet hit and proactively harden or monitor those appliances. Or if stolen credentials for their company are found, beyond resetting those, they might decide to roll out phishing training or tighter 2FA because it indicates targetting. In essence, defenders should have a playbook for common dark web findings: stolen creds > incident response, leaked client data > inform stakeholders, mention of attack planning > beef up monitoring, etc. The dark web intel should correlate with internal logs too. If you find evidence on a dark web search that, say, Access to CorpX network for sale includes RDP credentials, then you can double check internal logs around RDP usage or possible breaches around the timestamp. This cross correlation can confirm whether the sale is real, maybe you find an unaccounted login in your logs, aligning with the timeframe of the dark web post.

6. Stay Updated on Search Tool Changes: As the earlier section on trends suggests, the tools themselves will change. Defenders should keep abreast of new search engines, or updates to existing ones e.g., if Haystak adds a feature to search Bitcoin addresses in darknet context, that’s something an incident response team might want to use after a crypto theft. Subscribing to threat intel newsletters, or simply periodically reading cybersecurity blogs which often do Top Dark Web Engines updates can help the team know what’s out there. Some engines might shut down unexpectedly, having alternatives pre-vetted is important. It’s somewhat analogous to how threat intel folks track forum migrations similarly, track search tool migrations. Being agile and not dependent on any one platform ensures continuity of your dark web visibility.

7. Collaboration with Law Enforcement: If a defender finds something truly significant like a threat to life, or a large cache of customer PII, they should be prepared to involve law enforcement. Many government agencies actually appreciate when companies come forward with intel it might fit into a larger puzzle they’re solving. Dark web search findings can and have kickstarted investigations for instance, finding a trove of credit card numbers might lead to a ring of skimmers. Defenders should have contacts or at least know where to report e.g., in the U.S., the FBI or Secret Service for financial crimes, in the EU, Europol or local cybercrime units. When approaching law enforcement, being able to provide the source citation onion URL, how it was found, and any screenshots or evidence carefully sanitized of any illegal images helps them act on it. That said, defenders should also consult with their company’s legal and management before sharing information externally, especially if it involves customer data privacy obligations still apply even when the data is in criminals’ hands.

In essence, the rise of powerful dark web search engines has armed defenders with a flashlight in a dark room full of threats. But using that flashlight effectively requires training, rules, and a strategic mindset. Those organizations that invest in this capability will be a step ahead of attackers turning the dark web from a mysterious threat realm into an actionable intelligence source. Just as one would monitor network logs or threat feeds, monitoring the dark corners of the internet is now part of a well rounded defense posture.

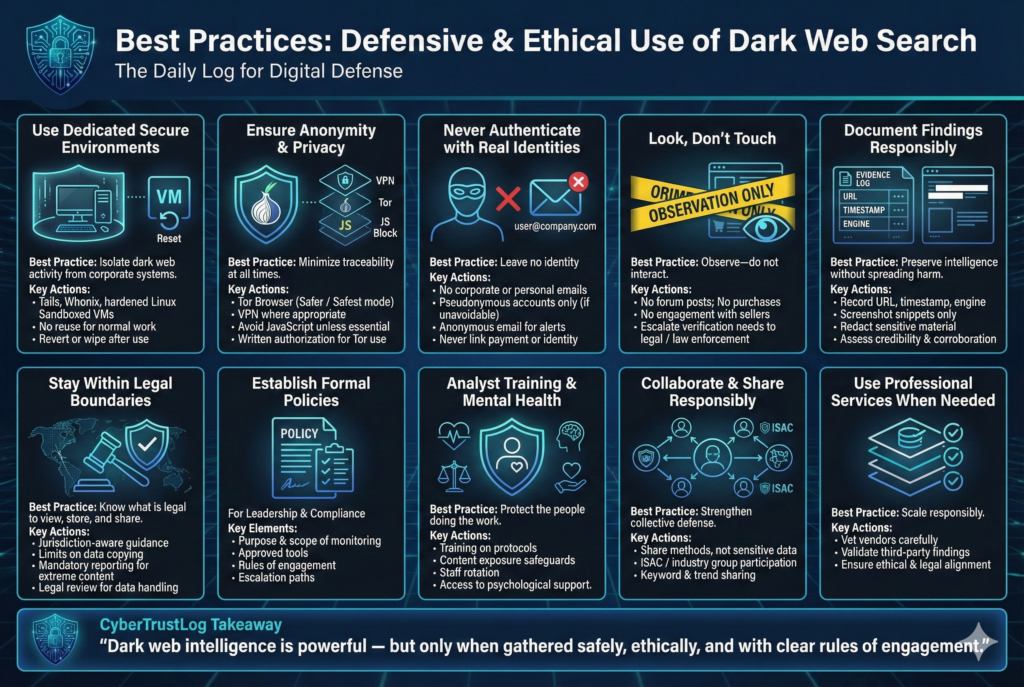

Best Practices Defensive & Ethical

To safely and effectively leverage dark web search engines for cybersecurity purposes, organizations and individuals should adhere to a set of best practices. These ensure not only operational security but also ethical and legal compliance:

For SOC Teams and Threat Analysts:

- Use Dedicated Secure Environments: Always conduct dark web searches on a segregated system. This could be a USB bootable OS like Tails, or a sandboxed virtual machine running a privacy focused OS e.g. Whonix or Kali Linux with Tor. This environment should not be used for regular work or tied to corporate networks. Its sole purpose is dark web reconnaissance, which limits the impact if malware is encountered. Once you’re done, consider reverting or destroying the VM snapshot or rebooting Tails, which by design wipes data. This prevents any persistent compromise.

- Ensure Anonymity and Privacy: Use the Tor Browser for any access to .onion sites or even to clearnet portals of dark web search engines. Even if you’re using a search engine’s normal web interface like ahmia.fi, do so through Tor or at least a VPN. This hides your IP and also conceals your activity from your ISP or corporate IT monitoring which might flag Tor usage. In corporate settings, clear it with your security management to use Tor and have a written exemption if needed so it’s not mistaken for an employee going rogue. When using Tor Browser, set security to Safer or Safest disabling JavaScript and other risky features by default. Only lower it if an absolute necessity e.g., a search site doesn’t function without it, and even then, weigh the risk.

- Never Authenticate with Real Credentials: Do not log into any dark web site with real emails or accounts. If a search engine offers login most don’t except maybe for premium, use pseudonymous accounts created solely for that purpose, and via Tor. For email alerts like Haystak offers, use an anonymous email, maybe a ProtonMail or SimpleLogin alias created over Tor that cannot be linked back to you or your organization. The key is to minimize any data exhaust that could link your searches back to you.

- Adhere to Look, Don’t Touch: Treat dark web exploration as if you are visiting a crime scene: you’re there to observe and gather evidence, not to tamper or participate. Do not post on forums, do not engage sellers, and absolutely do not purchase illegal items or data as part of your investigation. If you think purchasing is necessary to verify something e.g., buying your own stolen data as proof, this should only be done in coordination with law enforcement and legal counsel, as there may be stings or legal traps involved. Generally, anything that feels like you’re crossing the line is likely to pause and seek guidance.

- Document Findings with Context: When you find something notable via a search engine, document the source with a citation and timestamp. For example, if Ahmia shows a credential leak, note the onion link and date, maybe screenshot the snippet. This is important both for internal use to track trends and verify later if needed and for possibly handing to law enforcement or including in reports. However, take care to sanitize any reports e.g., don’t include raw illegal images, and if posting to a wider internal audience, consider redacting sensitive content. The documentation should also include how certain you are of the data’s validity did you find multiple corroborating sources? Does the site appear legit or is it a known scam?.

- Stay Within Legal Boundaries: Know the law for your jurisdiction. For example, merely accessing a site is usually legal, but downloading data might be illegal if it’s certain types of content. In some places, even possession of stolen data can be legally problematic e.g., possessing lists of credit card numbers. Work with your legal team to define what is acceptable. For instance, maybe you’re allowed to copy 10 sample entries of leaked data to validate it, but not the entire database. Also, if you inadvertently encounter content that must be reported like CSAM, follow through with reporting it to appropriate authorities. Many countries have hotlines or cybercrime units for this. Ethically, remember that some dark web content involves human victims trafficking, abuse. If your work stumbles on such content, consider tipping law enforcement even if it’s not directly cyber related you could save lives. But again, do so in a way that doesn’t implicate you in any wrongdoing hence the importance of working with law enforcement, not independently.

For Cybersecurity Leadership and Compliance Teams:

- Develop an Official Dark Web Monitoring Policy: This policy should outline the purpose e.g., to identify and mitigate threats to the organization emerging from dark web sources, the scope of what analysts can do, and the rules of engagement. It should cover what tools are approved Tor Browser, specific VPNs, search engines, data handling procedures, and the escalation path when something significant is found. Having this in writing protects the analysts they are operating under guidance and the organization demonstrating due diligence and clarity. Regulators and auditors are increasingly interested in cyber threat intelligence processes, a formal policy shows maturity.

- Training and Mental Health: Don’t overlook the well being of the analysts. Dark web investigations can expose individuals to disturbing content far beyond the level of gore or depravity one sees on the surface web. Regularly rotating staff or providing psychological support is advisable, much as it is for police investigators who handle child exploitation cases. Ensure analysts know they can ask for help or opt out if they encounter something traumatic. Also train them on how to react calmly e.g., the first time someone stumbles on a site with violent content, they should know not to panic and accidentally click anything or close things unsafely, they should follow protocol which might be to disconnect and alert a teammate to double check, etc..

- Coordinate with Peers: Within industry groups or ISACs Information Sharing and Analysis Centers, share non sensitive findings and techniques. Many organizations are grappling with dark web monitoring, by sharing experiences e.g., We found success using search engine X for credential stuff, but engine Y is better for carding info, you contribute to a collective defense. However, be careful not to share sensitive company specific info on these channels and focus on methods and general trends. Some communities even share watchlists of keywords relevant to their sector that are worth searching periodically.

- Leverage Professional Services as Needed: If your team lacks the bandwidth or skillset to do deep dark web dives, consider using reputable threat intelligence services that do this for you many were mentioned earlier Recorded Future, etc.. They often use the same search techniques but at scale and with expert analysts. Even if you outsource, it’s good to have at least a basic capability in house for quick checks and to validate third party reports. Also, ensure any third party you use abides by legal/ethical guidelines you’re comfortable with, you don’t want to be indirectly funding illicit activity through a contractor.

- Transparency and Respect for Privacy: If you’re an enterprise monitoring the dark web for your employee or customer data, handle any findings with care. For instance, if you discover an employee’s credentials on a hacker forum, approach that delicately involving HR if necessary, and treat the employee as a potential victim, not immediately as negligent, their password might have been stolen via malware. Similarly, if you find customer data, your legal team might decide if breach notification laws trigger. Under GDPR or other regimes, even data found on the dark web may require notification if it’s confirmed to be from your systems. The key is to respond ethically: the goal is to protect, not to punish those whose data ended up there unless of course it was due to an insider’s wrongdoing, which is separate.

For Compliance and Avoiding Going Dark: One interesting aspect Google shutting down its Dark Web monitoring for consumers implies individuals and small businesses might be left with fewer easy options. Cybersecurity professionals in those spaces should educate their stakeholders that just because Google isn’t watching their data doesn’t mean nobody is. Encourage use of HaveIBeenPwned and other services for basic monitoring, but also consider if some dark web search can be done for high risk individuals like perhaps doing an annual dark web scan for executives’ personal info, as part of executive protection programs.

In summary, best practices revolve around protecting yourself while you gather intelligence and using that intelligence responsibly. The dark web is one of those environments where the usual cybersecurity dictum the attacker only has to be right once, the defender every time kind of flips when you’re exploring one wrong click by the defender researcher can cause compromise. So meticulous care and a strong framework of do’s and don’ts are the defender’s shield. With these best practices, security teams can harness the power of dark web search engines effectively without undue risk.

FAQs

Are dark web search engines legal to use?

Yes, in most jurisdictions simply using a dark web search engine is legal. These engines are tools that access publicly available albeit hidden information. However, what can be illegal is the content you might click on. For example, if you knowingly access or download illegal content such as child exploitation material or illicit drugs listings with intent to buy, that crosses legal lines. So while searching is not a crime, users must be careful not to engage in illegal activities. Always familiarize yourself with local laws. Many law enforcement agencies actually utilize these engines themselves for investigations, which underlines that the tools are legal, it’s the actions that matter.

How do dark web search engines work differently from Google?

Dark web search engines use custom crawlers that operate over anonymity networks like Tor or I2P instead of the regular internet. They can’t rely on standard internet infrastructure, no DNS, etc.. Instead, they start from known lists of onion sites or user submissions and then follow links between hidden sites where possible. The crawling is much slower due to Tor’s latency, and many sites require special handling, some might block or trap crawlers. Additionally, dark web engines often have to deal with a lot of junk scam sites, clones, and short lived pages far more than Google does, so their indices can get stale quickly. Also, unlike Google, which filters out illicit content and can rank by popularity, dark web engines might either filter based on safer criteria Ahmia removes illegal stuff or not filter at all Torch. None of them has the sophisticated ranking algorithms Google has, often results are just keyword matches by date. In summary: they operate in a more constrained, hostile environment and their coverage of content is a smaller, less optimized subset compared to the vast and cooperative surface web Google indexes.

Do I need the Tor Browser to use dark web search engines?

To access the search results on onion sites, absolutely yes you need Tor or an equivalent like Orbot on mobile, or a Tor gateway. However, a few search engines provide a normal web interface for searching. For instance, Ahmia has a clearnet site ahmia.fi where you can type queries and it will show onion links as results. You could use a regular browser for that initial search. But the moment you want to click through to the actual dark web page, you’ll need to be on Tor. Some engines also have Tor2Web style proxies which let you access onion links via a normal browser through a proxy server but using those is not recommended because they strip away the anonymity of Tor and may log your traffic. The safest workflow: use Tor Browser for everything if possible. If you use a clearnet search portal for convenience, treat it as a read only reconnaissance, then switch to Tor for exploring any result in depth.

Can dark web search engines index everything on the dark web?

No, not even close. They index only a fraction of dark web content, likely a small percent. Many dark web sites are unindexed on purpose: some require login or referrals search engines can’t get past login screens, some deliberately aren’t linked anywhere if no one submits or links it, a crawler won’t find it. Furthermore, Tor’s design of 56 character random addresses means there’s no way to enumerate all sites. It’s been described that searching the dark web is like shining a flashlight in a vast dark cavern where you only see the patch you shine on. So, while engines cover the more popular and longer standing sites markets, forums, wikis, etc., new or very secret sites might not appear. In fact, some criminals rely on this lack of indexing for security by only sharing links privately. Bottom line: if you search and find nothing, it doesn’t guarantee nothing’s there, it might just be hidden beyond the reach of current search engines.

Why do dark web search results often include dangerous or scam sites?

Because some search engines don’t filter content, buyer beware is the rule on dark web search. A query for something benign could still return malicious sites, phishing pages, or outright fraudulent links. For example, searching a Facebook account on Torch might yield a result claiming a Facebook account hacker tool which is likely malware. The dark web isn’t regulated, and search engines like Torch or Haystak choose to index almost everything for completeness. They present results without the kind of safety flags Google might have. Additionally, criminals create lots of decoy or clone sites e.g., multiple AlphaBay markets after the real AlphaBay was shut down, to scam users and these inevitably get indexed. The search engine isn’t sophisticated enough to always tell real from fake that’s up to the user’s judgment. That’s why using trusted indexes Ahmia with filtering, or known official link repositories is important if you’re not seasoned in dark web navigation. It’s also why one of the safety tips is don’t blindly trust search results, double check if possible via multiple sources.

Is DuckDuckGo’s onion service a dark web search engine?